It’s hard to imagine a more powerful symbol of self-reliance, strength, and determination than the cowboy. While the archetypal cowboy is a highly romanticized figure, and one that ignores ugly truths about the cost of westward expansion in the United States—namely the theft of Native American lives and land—still it has become synonymous with traits we almost universally admire. And while the archetypal cowboy is almost always depicted as white, in reality no one better embodies these admirable traits than the Black cowboys who helped shape the culture of the American West.

According to the late historian William Loren Katz, whose book The Black West tackles the whitewashed mythology of the American frontier, people of African descent “rode every wilderness trail—as scouts and pathfinders, slave runaways and fur trappers, missionaries and soldiers, schoolmarms and entrepreneurs, lawmen and members of Native American nations.” Although their stories have largely been untold, more than eight thousand Black cowboys rode in the western cattle drives of the late 1860s. It’s my privilege to introduce you to the men and women who carry on their legacy today.

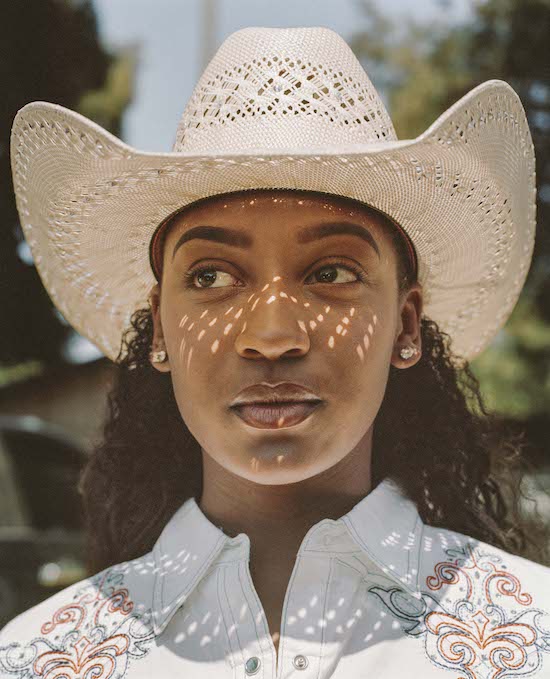

I have been documenting Black cowboys in the San Francisco Bay Area at the annual Bill Pickett Invitational Rodeo since 2008. The families who return to the rodeo each year come to support one another and the other contestants. It’s a testament to their commitment not only to the sport, but to their community. The bonds that are forged at the rodeo are undeniably strong. As cowboy Jamir Graham said to me recently, “My rodeo team is my family.”

[photo above] Joseph “Dugga” Matthews (far right) stands on his horse in 2008 with a group of riders from Stockton, California, who are part of the Brotherhood Riders group. Dugga is a horse trainer, farrier, and veterinarian. He came to the States from Antigua in 1998 and has been attending the BPIR ever since.⋅

It was the intimate moments behind the scenes, the quiet time the riders share with their horses before a competition, and the relaxed atmosphere when the rodeo has ended that lured me to document the contestants and the attendees many years ago. The beauty of the bonds they’ve formed—with the horses and with the other riders—continues to astound me. The intimacy, trust, and understanding are palpable both on and off camera.

[photo above] Mother and daughter cowgirls from Atlanta, Adrian Vance and Ronnie Franks (in red), sit behind the scenes, where contestants watch the spectacle in the arena. “Black rodeo is a celebration of African American history and culture. We ride on behalf of those who did not have the opportunity to do so,” says Ronnie, thirteen years after this photo was taken in 2008. “Lu [Vason, BPIR founder] would have been proud to see this book published.” ⋅

The rodeo itself is named after a famous Black cowboy. The legendary Bill Pickett was the first Black rodeo athlete to be honored in the Rodeo Hall of Fame in Oklahoma City; he was inducted in 1971. The Miller Brothers recognized his talent in 1905 and hired Pickett to travel with them as a performer and exhibitionist in their 101 Ranch Wild West Show. Pickett was famous for grabbing a steer’s lip with his teeth—a feat known as bulldogging, as that is what bulldogs would do while herding steers—and became well known for being a fearless and skilled rider. At the time, Pickett did not participate in the rodeos, as Black cowboys were not allowed to take part in the main rodeo and had to compete after the crowds had left. But at the Wild West Show, people from all over would come to admire his bulldogging and bull-steering skills as part of the show. The audience didn’t seem to care that Pickett was Black. They were enthralled by his talents.

[photo above] Iyauna Austin wears a custom-made skirt to the BPIR’s 35th Anniversary Rodeo in Oakland in 2019. “My grandmother, Juanita Brown, and I wore the African print skirt at the Black Cowboy Parade,” Iyauna explains. “Some people requested we wear it again at the Bill Pickett Invitational Rodeo, and we did. It’s an exciting experience. People get to see you on your horse. They get to see the hard work you put into your horse to make you look good. What you wear also helps your horse. Your horse makes you look good. And then you have to try and make your horse look good. So it’s really exciting. We wait all year for the rodeo, and then it finally happens.” ⋅

The Bill Pickett Invitational Rodeo (BPIR) was founded in 1984 by Lu Vason, and to this day it remains the nation’s only touring Black rodeo. A hairstylist, concert producer, and promoter, Vason became interested in rodeos while attending the granddaddy of them all: the Cheyenne Frontier Days rodeo in Wyoming. He quickly realized that there were no Black cowboys participating in that legendary production. On his return to Denver, where he resided in the 1980s, he began his research at the Black American West Museum, exploring the history of Black cowboys, the contributions of African American settlers, and the opening of the western frontier. After more than two years of research and fundraising, Vason produced the inaugural Bill Pickett Invitational Rodeo in Denver, Colorado. This heritage rodeo helps educate people from all over the world about the rich history of Black cowboys and cowgirls, and it highlights their overlooked contributions to American rodeo culture.

[photo above] Cowgirl Brianna Owens traveled from Houston, Texas, to compete in the ladies’ barrel racing at the BPIR in 2017. Barrel racing is one of the two events open to cowgirls only. The other is ladies’ steer undecorating.⋅

The modern rodeo I’ve witnessed annually at Rowell Ranch Rodeo Park, just outside of Oakland, California, is a study in generational shifts. As young contestants enter this traditional competition, they bring with them new perspectives and styles. Gucci sunglasses and Stetson hats, cell phones and lassos, Louis Vuitton saddles and Wrangler jeans—it’s clear that something completely new is being forged in the collision of classic and contemporary. And not only are the riders inventing a new aesthetic, but they are exploring what it means to be a cowboy in contemporary America, in and out of the arena.

Many cowboys and cowgirls believe the sport has saved their lives, and all of them recognize the intense discipline needed to keep and care for their horses. That discipline requires passion and commitment in equal measure. Oakland native Brianna Noble explained, “I am really just so grateful that I could have such a positive addiction, because I really think that horses are actually, truly a drug and addiction in the most positive sense of it, you know. They really have kept me on the straight and narrow throughout my life and taught me an unmatched work ethic, and really just kept me into all the positive things in my life.”

[photo above] Prince Damons, Cowboy Sam, and Cowboy Jonathan Higgenbotham parade their horses at the Grand Entry of the BPIR in 2019. This is the most anticipated event at the rodeo, where guests are able to observe and celebrate the entire cowboy community, regardless of their participation in the competitive events. Riders glam up themselves and their horses to look their best. ⋅

The people who gather annually for the rodeo make up one of the most lively, bighearted, kind, and compassionate communities in the Bay Area. Many cowboys and cowgirls also run year-round youth programs—Brianna Noble’s Mulatto Meadows, Sam Styles’s Horses with Styles, and the Spurred Up program, for example—that offer inner-city kids the opportunity to work with horses as a form of therapy. “I’m always looking for the next thing to help these kids. I’m looking for the next way to get another kid here,” said Styles of his youth program. “Riding is not for everybody. And I know I can’t save every single life. But if I could get one more kid here and keep them off the streets of Oakland, or be able to get them away from what they’re going through at home, in a troubled situation—I mean that’s just one more kid who could have a different outlook on life.”

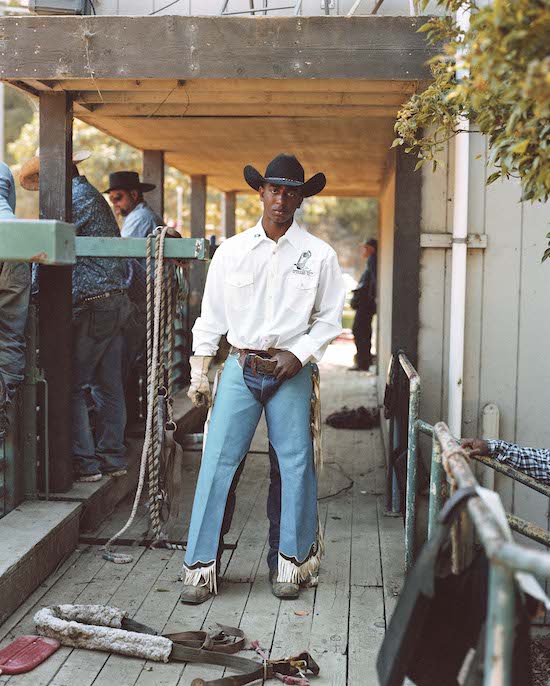

[photo above] Cowboy Jamir Graham nervously awaits his turn to compete at the thirty-second annual Bill Pickett rodeo in 2017. This was Jamir’s first racing competition at the BPIR. He was sponsored by his youth program, Spurred Up. “I participated in bareback riding and relay racing. I was also the flag bearer with the Spurred Up flag for the Grand Entry,” he remembers. “I was born into riding. Growing up, my mom and grandfather competed. So for me, BPIR has always been a big family reunion.” ⋅

For decades, these urban cowboys have found joy in the traditions passed down by their predecessors. I have gotten to know many of those who participate in the rodeo, most of whom have a strong network of friendships in the Bay Area. Throughout my twelve years of attending the rodeo, my friendship with the cowboys has brought me closer to their communities and families. They have invited me to their ranches to see them ride and care for their horses outside the arena. I’ve taken hundreds of pictures over the past decade that document the talent, dedication, and love of this community. It’s a dream come true to share their passion and skill with the rest of the world.

I hope my images inspire you to follow your own passion and joy, as the cowboys have inspired me.

[photo above] Ron Hill Jr., photographed here in 2018, competes regularly in steer riding at the BPIR. At age seven, he was the calf-riding champion at the Pacific Coast Junior Bull Riders. His father, Ron Hill Sr., explains: “I met my wife at the BPIR in the City of Industry back in 2009. We hit it off and created a young cowboy of our own. Ron Hill Jr. started off as an infant riding in my arms around our property. By the age of three, he was competing in rodeos riding sheep. By the age of five, he started riding calves and steers.” ⋅

__________________________________

Excerpt from The New Black West: Photographs from America’s Only Touring Black Rodeo by Gabriela Hasbun, published by Chronicle Books 2022.

Top photo: Robert “Cowboy” Armstead, here in 2018, a retired racehorse groomer from Stockton, California, is eager to keep Black cowboy history alive in the West. He was the groomer for Foolish Pleasure at the Kentucky Derby in 1975. “Working the racetracks was the life,” he says. “Traveling town to town, city to city, making all this money. Working the tracks was really good. I love horses. I would do anything in the world to be around them all the time.”