Earlier this year, I sat with Avery Trufleman, host and producer of the fashion podcast Articles of Interest, at a university campus to talk about the origins of trends. As many readers know, Articles of Interest is a fashion podcast that takes deep dives into the stories behind what we wear. When the show started, it was a miniseries under the 99% Invisible podcast umbrella, but the show is now owned by Avery.

I’ve called Articles of Interest the smartest podcast on fashion—and still stand by that—because Avery has the unique ability to synthesize large, complicated issues into easily digestible 45-minute episodes without losing the heart of what makes these topics so interesting. Every episode has something for neophytes and experts alike—stories that explore the personal and historical, and the intersection of clothing, society, and politics.

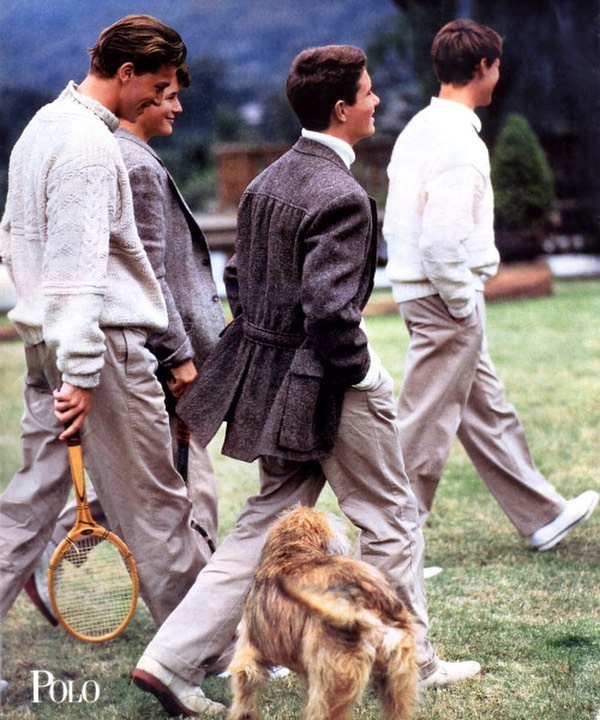

When we sat down for an interview, I was told that the new season was going to be about the origin of trends. But at some point in the discussion, Avery asked if I thought prep was coming back. “I don’t think so,” I told her. Much of prep references a long-lost, WASPy Northeastern culture that has become somewhat off-limits. We’re (rightfully) more attuned to the problems of inherited wealth and privilege, and few people want to dress like a 1980s film villain. At the same time, I added, prep never really went away and is still around us. When I said that, I remember looking across the university campus and seeing students rushing to class while wearing collegiate sweatshirts, button-down shirts, and flat-front chinos.

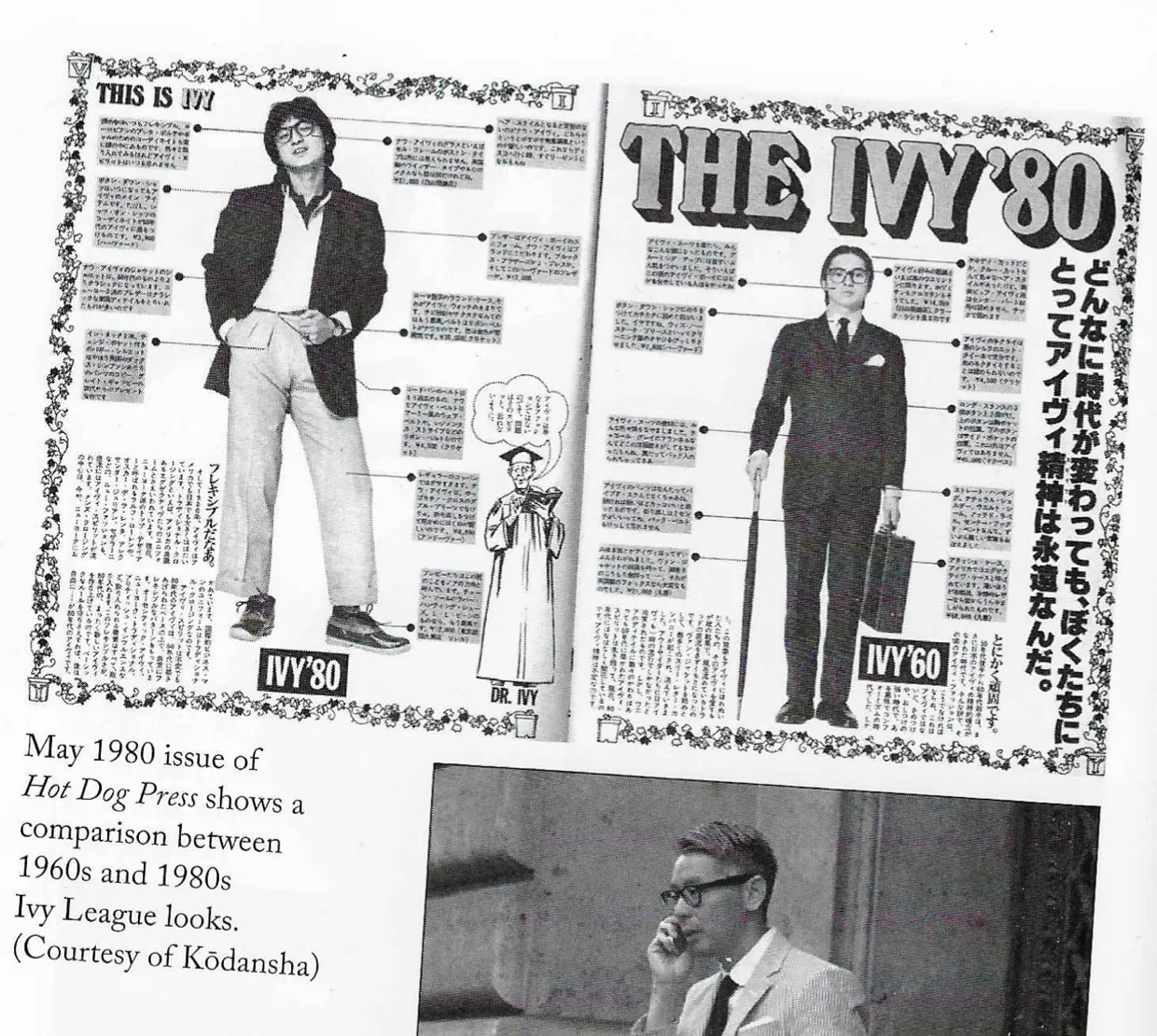

Months later, Avery told me that the new season of Articles of Interest will be entirely about prep—the history of the style, how it spread into different parts of American and global society, and whether it will come back as a trend. The seven-part series—with the last episode coming out this Wednesday—is the smartest podcast distillation of this style I’ve come across. It features an all-star line-up of guests, including Brooks Brothers’ new CEO Ken Ohashi, J. Press’ Richard Press, Ametora author David Marx, Harper’s Bazaar Fashion News Director Rachel Tashjian, and others. Like other seasons of Articles of Interest, it has something for everyone (including people who remember poring over scanned images of Take Ivy on The Trad before the book was re-released). Below is a transcription of an interview I recently did with Avery about the new season.

Derek: You originally wanted to do a series about trends. How did it move to Ivy?

Avery: The past two seasons of Articles of Interest were organized so that each episode functioned as its own little story, so you didn’t have to listen to the episodes in order. But if you did listen to them in order, they stack on top of each other and form a thesis. Season one is about the fundamentals and textiles; season two is about luxury. So when it came to season three, I thought I’d make it about taste and trends. One episode was going to be about choker necklaces, and another was going to be about Ugg boots. Each episode was going to explore the anatomy of a fad and why we like the things we like. With so much nostalgia in the air, I figured this would be the best of both worlds.

So one of the episodes was going to be about preppy style. But as I was doing research for this episode, I was like, “holy shit, this is the most important thing!” I keep coming back to this metaphor: in the way that you have to look at whiteness to look at race, or look at masculinity to look at gender, you have to look at preppy style to understand all of the countercultural fashion movements of the 20th century.

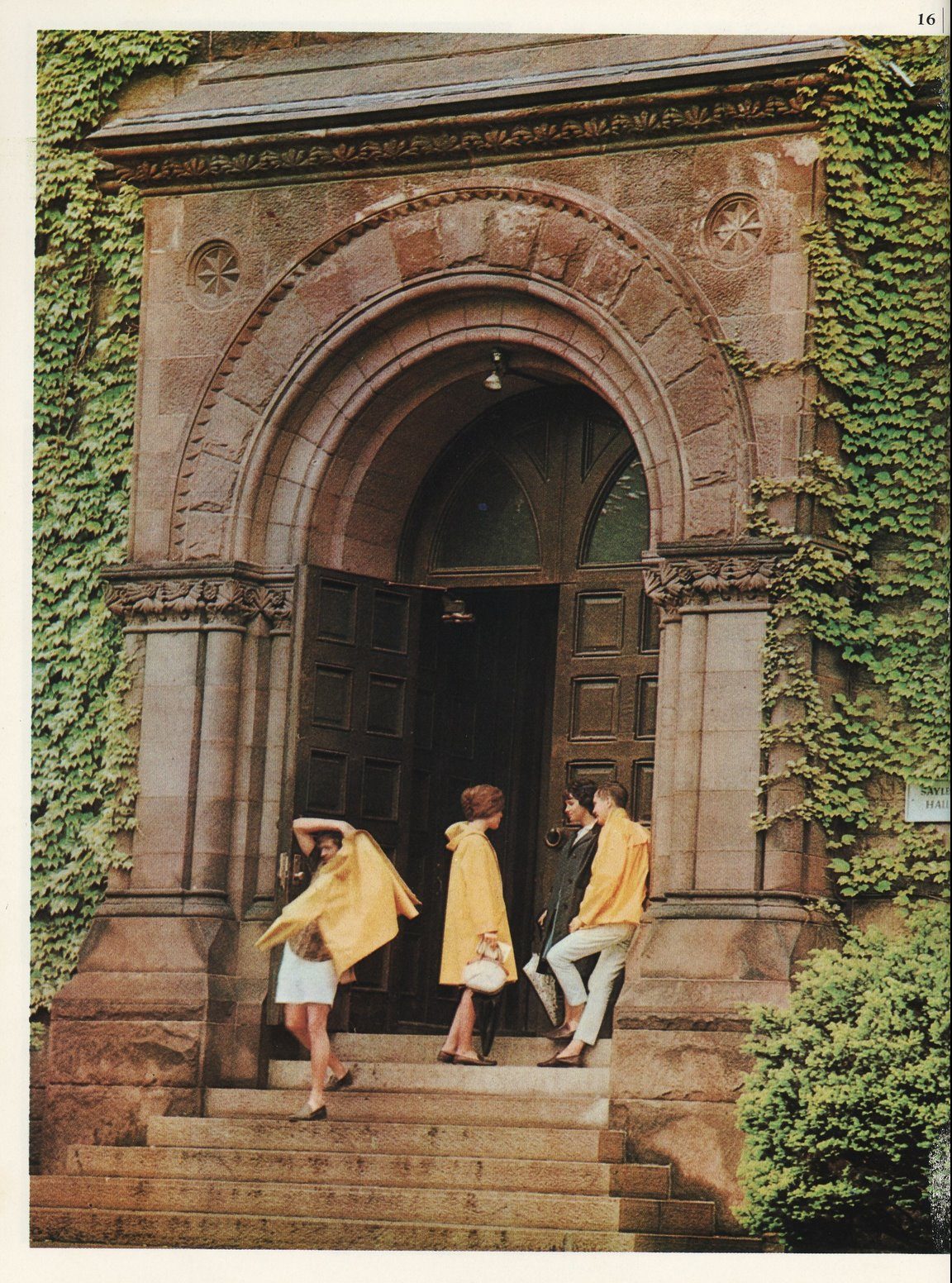

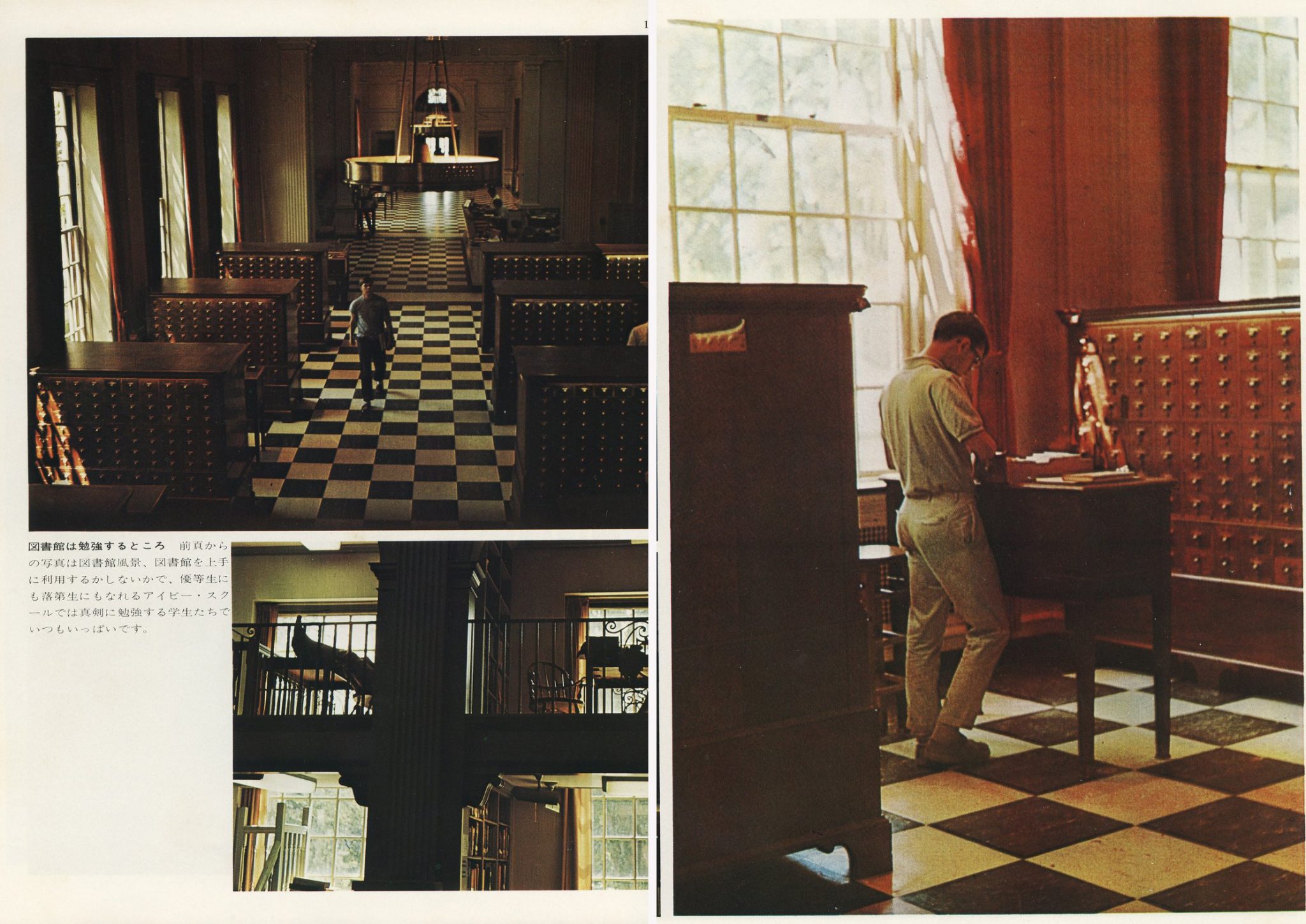

I think preppy style is part of our lives in a way that sometimes we don’t even recognize. When I interviewed you for this season, I remember you said, “Ivy is now just clothes. Flat-front chinos are just pants; a button-down shirt is just a shirt.” That made me look at the world anew, and it took me a while to figure out how to weave in all the different parts of this story. There’s the story about how Ivy Style was worn at Princeton, the part about how it landed in Japan, the part about Black Ivy, and the part about Jewish tailors. There are so many interweaving parts, but they create this one story about the rich tradition of American-style clothing that has become so present in our lives.

Derek: Am I correct in thinking you grew up in that school system and culture?

Avery: [Laughs] Yes, I’m from Westchester; I’m from the preppy cradle. I went to a prep school with a stringent dress code, and dressing preppy was the path of least resistance. I hated it there because I felt like I didn’t belong for many reasons that are insufferable to talk about. So I took the long and circuitous route around this dress code. I spent a lot of time on Haight Street because my aunt lived in San Francisco. When I would visit her, I’d go shopping for flapper dresses, which I would wear back home with cowboy boots and hippy beads. These were wild clothes. I remember it got to one point where, on Halloween, no one knew I was wearing a costume because I dressed ridiculously all the time.

This gets to something we talked about a few years ago when you mentioned to me that clothing is about semiotics, and when you put together an outfit, you’re crafting a sentence. And it’s possible, as Noam Chomsky posits, to craft a grammatically correct sentence that doesn’t mean anything. When I was finally revisiting all this, I was like, “oh, my outfits were the fashion equivalent of ‘colorless green ideas sleep furiously.’” My outfits didn’t make sense, and I was alienating people. I rebelled against this preppy archetype I didn’t know enough about.

Looking back, I’m sure many kids at my prep school also felt they didn’t belong for many different reasons. And I was judging them for wearing clothes that provided them with so much comfort. Once I looked deeper at these clothes, I started to understand that they’re not just for people who want to look like rich white men. I mean, they are definitely for people who want to look like rich white men—but they’re also for a much broader cross-section of people. When I finally understood the whole story about this clothing style, I bought some stuff from J. Press. And I love it! I’ve integrated it into my life. It feels nice; it feels part of who I am.

Derek: What was the dress code at your school?

Avery: You had to wear collared shirts, and you had to tuck them in. You couldn’t wear jeans or shirts with writing on them. A skirt had to be a certain length; you had to cover your shoulders. The code wasn’t wild, but when I was in public school, I wore band t-shirts that said The White Stripes and called it a day. That was my semiotic signaling. So weirdly, everything I learned about clothing as a means of expression was a reaction to preppiness.

Derek: So, how is this season organized?

Avery: The first episode is about trends and their origins, and it introduces the book Take Ivy. Then the next six episodes go through the history of Ivy almost chronologically, but it goes back and forth with the story about Japan’s relationship to this style. For example, part two is about the Meiji Restoration, the birth of Ivy, and the origins of Brooks Brothers. Part three is about the GI Bill and the Golden Era of this style, when Ivy Style spread into the middle class, historically Black universities, and women’s universities. Part four is about the making of the book Take Ivy, the counterculture movement, and the start of Ralph Lauren. Part five is about how Van Jacket gets popular and The Preppy Handbook. Then we have the rise of Ralph Lauren and the Lo Heads. Finally, the last episode is about the early 2000s prep revival.

Derek: You mentioned that you’ve gained an appreciation for prep in making this show. In what ways do you see prep differently now?

Avery: I’ll tell you a story. I remember when I went to J. Press to speak to Richard Press. I felt like I had snuck into the inner sanctum of a Freemason’s meeting house because so many long-time J. Press customers came in to kiss the ring. Richard has so many fans, and it was so cool to see.

I remember a few months ago, when you were talking about Shein on Twitter, you said that the best way to love your clothes is to develop a sense of association or meaning attached to those clothes. And once I learned the backstory of J. Press, I couldn’t help but love the company. I learned that Jacobi Press was a Latvian Jewish immigrant who hired tailors that survived Auschwitz. That’s an incredible story—and it’s much closer to my family’s history. That backstory made me feel more connected to the clothes than my previous association with it, which was the idea that Ivy is only for preppy kids who have Sweet Sixteens on yachts.

Knowing that story, I bought a J. Press tennis sweater. I wore that same sweater when I Interviewed Lo Head Dallas Penn. When I saw him, he said right away, “that’s a great sweater.” It just made me realize that this style is in dialogue with so many different people. So even though Ivy is the embodiment of assimilation, it’s also the lingua franca of fashion. It’s a way to say, “hey, I tried.” There’s a reason why this is the default style for business casual, job interviews, and date nights. Dallas Penn said, “This is what you wear when you want to say, ‘trust me.’ Or ‘hi, how are you?’” I love that.

Derek: Do you feel prep is coming back?

Avery: I think it’s important to recognize there’s such a profusion of trends. I don’t know if any style dominates the conversation, but I believe preppy is more en vogue than it was five years ago. One of the reasons I started thinking about this is because trend forecasters have been saying preppy is coming back. Even on the streets of New York City, I see a lot of dudes in polos and loafers. You also see it with the J. Crew revival and all the talk about Aime Leon Dore ….

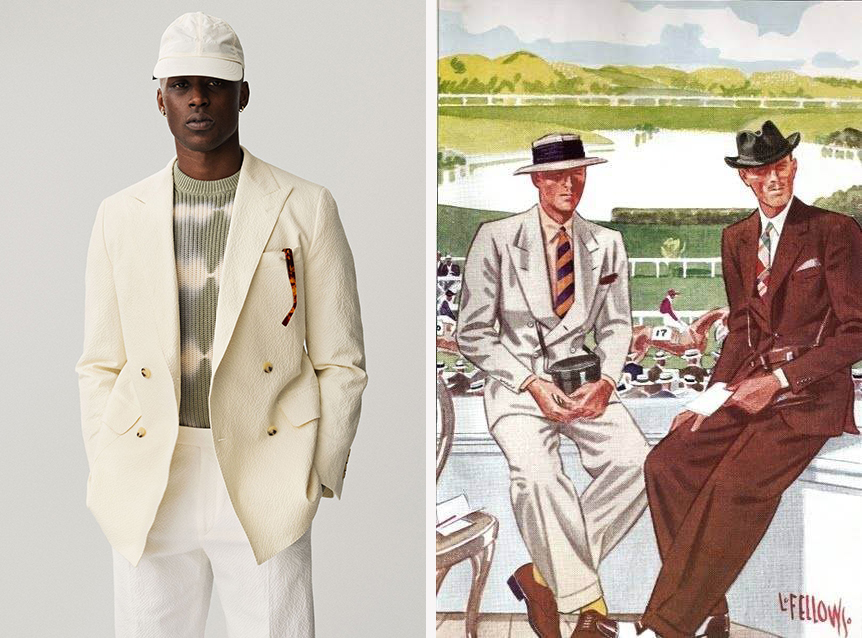

Derek: That’s one of the weird things about Aime Leon Dore. That brand is just repackaging Ralph Lauren, and RL is just repackaging Brooks Brothers. When you flip through their lookbooks, you see patchwork madras pants, tennis sweaters, tweed sport coats, spectator loafers, and so forth. But no one calls them a preppy brand. Many people don’t even recognize the connection between ALD and Ralph Lauren, let alone ALD and Brooks Brothers. That’s one of the fantastic things about Ivy. It’s constantly repackaged to mean different things—the sleaziness of 1980s greed or, in ALD’s case, the youthfulness of 1990s street culture.

You even see it with Emily Bode, who recently won the CFDA’s American menswear designer of the year for the second year in a row. There’s no doubt that BODE has done some incredible things for menswear, including popularizing patchwork clothes and university cords. But those things are also prep! Patchwork madras and tweeds are the style of Chipp, J. Press, The Andover Shop, and so forth. We’re constantly pulling the same familiar items; we’re just giving them different meanings. So prep is never entirely dead because these items are like the ABCs of American clothing language.

The one thing that makes me doubt that preppy is back, in the real sense of being back, is that we still don’t explicitly reference rich white culture in fashion advertising. At least outside of Ralph Lauren. So much of fashion is about buying into a fantasy. You wear something with the idea that you’re like so-and-so person. You might wear a Cartier Tank to think you’re like Andy Warhol. Or you wear a black double rider to believe you are like Sid Vicious. At the moment, very few companies reference true preppy culture as it was referenced in the 1980s or early aughts. Very few people are wearing prep with the aspiration that they’re part of a WASP tradition. That community has little cultural cache at the moment.

The only thing that makes me think actual prep might come back is when I think about the 1980s revival, which surprisingly came after the countercultural revolution of the previous decade. It’s like, after ten years of challenging social norms, somehow people got into dressing super heteronormative. It was like whiplash: one moment, people are challenging all of these norms, and the next, they’re celebrating Old Money lifestyles and Wall Street greed.

Avery: I talked to Bruce Schulman and Rick Perlman about what happened in the 1980s; they have a fascinating theory. They believe it has to do with Charles Schwab and Fidelity. In the 1980s, these companies opened the financial markets to the masses. Suddenly, anyone could enter this world formerly reserved for rich people and play the market by calling this 1-800 number.

It’s interesting because it almost parallels how preppy spread with the GI Bill, when the masses were allowed into this elite world of education, and people who thought they could never attend college finally got a chance to go. Then in the 1980s, people who thought they could never have access to brokers suddenly had access to passive income. With that came the feeling that you also have the right to the Old Money look. They were like, “I, too, am a monied person; I just need the costume to back it up.” I’m so fascinated with how these social changes affect our fashion choices. If preppy is back—and that’s a big if—I wonder if it has to do with this new money free-for-all we’re seeing. People are becoming millionaires overnight by investing in Gamestop or being on OnlyFans, and I wonder if the accruement of wealth is forever married to this style.

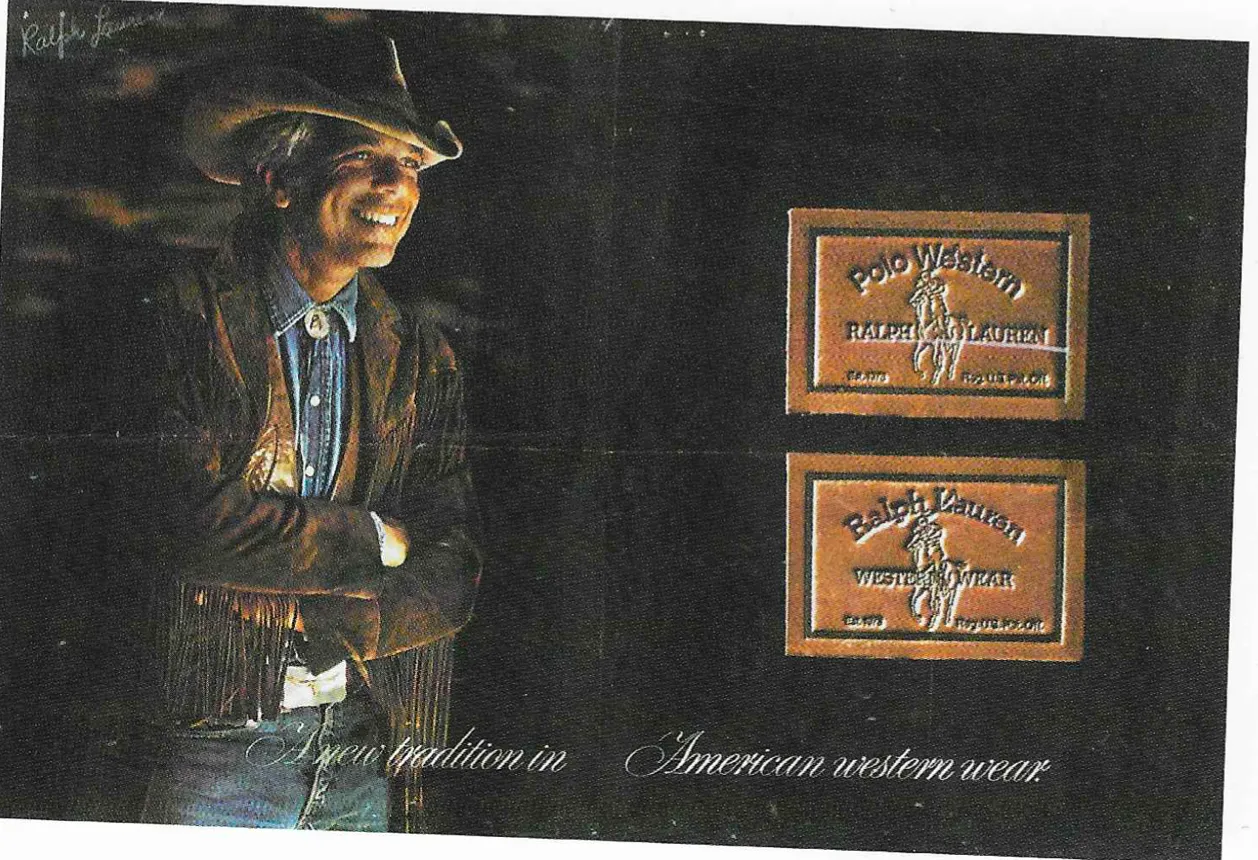

The main story of this season is about how socio-political forces make this look go away and come back. But there’s also this story about the transition from Brooks Brothers to Ralph Lauren. I used to think those two companies made boring clothes that were not for me. As someone who created RL Pics That Go Hard, you certainly know this more than I do, but I didn’t appreciate the magnitude of what Ralph Lauren has done as a designer. When I learned more about it, I was like, “this is definitely an Articles of Interest story. This guy is the Steve Jobs of fashion.”

Derek: A journalist contacted me about that Twitter account and asked me what I liked about Ralph Lauren. For me, Ralph Lauren, as a fashion brand, embodies America. In the sense that America has a general identity, but it’s also made of so many other kinds of identities. That, to me, is Ralph Lauren. There’s an RL aesthetic that’s basically about affluent WASP lifestyles. At the same time, everyone takes part in that aesthetic and makes it their own. I think that’s also true of American identity. White culture holds a certain kind of hegemony in our society, but American culture is also a lot richer and more diverse than just white culture. People are remixing white culture with their culture and are turning it into different, uniquely American things. It’s the same as how Ralph Lauren represents both whiteness and non-whiteness. That’s what makes Ralph Lauren so special to me. Brooks Brothers defined American style because they gave us the vocabulary and syntax when they imported things such as tweed jackets, Shetland sweaters, polo coats, Madras, penny loafers, and such. But Ralph Lauren embodies American style in terms of spirit.

Avery: Dallas Penn put it nicely when he said, “you feel safe in the world of Ralph Lauren.” Ralph Lauren helped people understand different archetypes—cowboy, safari, prep, trad, and so forth. Walking through a store is like walking through Epcot center. That’s an incredible fashion literacy that he gave to people.

Derek: So you’re currently editing the last episode?

Avery: Yea, in the last episode, I revisit my old prep school. The school got rid of its dress code, but kids were still in prep, which shows how time, place, and occasion still influence how we dress. But they’re remixing prep in their way. They’re wearing things like polos with sweatpants and sneakers. I remember seeing this student in seersucker shorts—which is crazy because you can wear shorts now since there’s no dress code. She said something like, “yea, I’m trying to do this 2012 look.” That was the oldest I’ve ever felt—up there with when I found my first gray hair. It was so weird because I felt like I was seeing nostalgia being recycled before my own eyes. It was like a style being filtered through a game of telephone. And that’s my closing argument: this style will never go away because it’s stuck in a nostalgia feedback loop.

You can listen to the new season of Articles of Interest on Apple Podcasts or Spotify. There is also a Substack blog that accompanies each of the new episodes. The final episode comes out this Wednesday. Many thanks to Avery for taking the time to chat with me!!!

The post The Smartest Fashion Podcast Explores Ivy Style—And Asks If Prep Is Back appeared first on Put This On.