The charismatic, nomadic rewilder Finisia Medrano, who died of a heart attack on April 3, 2020 in Caliente, Nevada, was a towering figure among rewilding communities in the American West. Devoted to tending and planting native species and traditional staples such as biscuit root and fritillaria, Finisia was also a realist and accepted that increasing climate change meant that invasive plants have a part to play in the complex ecosystems of the West. She used her vast botanical knowledge to experiment with planting at different altitudes and in different seasons as a way of giving vulnerable species a chance to thrive.

In her trademark buckskin skirt, wide-brimmed hat and ever-present cigarette or joint lodged between thumb and finger, Finisia traveled on foot, in covered wagon, and by horseback through Nevada, Utah, and portions of Oregon, Idaho, Wyoming, Colorado, Montana, California and Washington state. For 35 years she followed a lifeway practiced for millennia known as the Hoop, a seasonal migratory way of living by following one’s food source, hunting, gathering roots, fruits and nuts, while planting seeds and propagating en route.

Finisia generously shared her vast knowledge of plants and their place in the web of life, but she could be equally generous with her sharp quips, her criticism of consumer culture and her impatience at the stupidity of humans. She could swear like no one else. Yet, her anger and frustration stemmed from her love for the natural world. When she spoke of “the refugees without legs,” her term for plants uprooted by mining, fracking, cattle grazing, escalating wildfires and the general encroachment of human activity, she would burst into tears. She was utterly connected to the Earth.

Finisia’s early life, recorded in her book Growing Up in Occupied America, and self-published in 2013, was not an easy one. Her father was a John Bircher—a committed anti-communist—whose union boss was gunned down in front of her childhood home in Vegas. After the shooting, Finisia’s father piled his family into the car and headed north “to the Coeur d’Alene reservation to live by my Stepmom’s parents. At this time, they were the only Indians I knew,” she wrote. And it was here in Idaho that Finisia began her real education at the knee of Native elders, whom she called her “other Grandmothers.” It was they who showed her how to pick the seed pods of yellow lilies, how to dig biscuit root, and it was they who sowed the seeds of Finisia’s political awakening to the fact that she was “living in Occupied America.”

Finisia generously shared her vast knowledge of plants and their place in the web of life, but she could be equally generous with her sharp quips, her criticism of consumer culture and her impatience at the stupidity of humans.The first time I met Finisia, in the Oregon desert, she told me how in the 1970s, pre-transition when she was a pretty young man with a surfer’s body and a Farah Fawcett flip, she dug a cave in Malibu with her hands and feet. It overlooked a beach called Pirates Cove and she lined it with pink carpet like a “giant pussy.” Finisia lived on mussels and seaweed. Visitors would bring LSD and beer. Her cave had a small walk-on part in the 1976 film Logan’s Run and it was here she met Bob Dylan who was building his Malibu home nearby. When Finisia told stories, they spanned time and space in a way that gave them the quality of myth.

Her early adulthood reads like a psychedelic film script, and yet her single-minded devotion to the Earth, and her brilliant ability with words are what gave the rest of her life its shape. While showing me how to dig biscuit root in Oregon, she recited her poem “Lamenting the Love of a Friend”: “They say I am mad, only half human / And half rabid bitch” it begins. And, indeed, she identified as much as a coyote, a shape-shifter, as she did a man or a woman.

Born in Vegas in 1956, downwind from nuclear testing, Finisia underwent sex reassignment surgery in the late 1970s paid for by her husband Max Miller, a wealthy PR man 45 years her senior. In 1984, after seven years with Max, Finisia headed into the mountains to try and kick her tobacco addiction. Instead she returned home a Christian. Max couldn’t live with a god-fearing partner, so Finisia signed the divorce papers, walked out of their Los Angeles house with a sleeping bag and a change of underwear, and just kept walking. This was the beginning of her life as a nomad. “I gave up everything for Jesus,” she told me. And shortly after this, she got herself a covered wagon upon which she painted in large letters: “Pulling for Christ Across America.” Finisia remained a Christian her whole life.

Along with her faith, Finisia was devoted to living in harmony with the planet in a way that aligned with her conscience. This required her to give back to the land more than she took and entailed traveling with her pack horses, replanting and tending what she called the “wild gardens of the West.” It is against the law to plant seeds on public lands, and Finisia was jailed twice for doing so.

In 2008, while serving time in Idaho, Finisia penned a manifesto in which she called her “planting back of the native food flowers … and berries without permit on public lands” both an “act of civil disobedience” and her “duty to God and to Earth.” She described “this hoop in the west” as “the last place on earth where it is even possible to live in that symbiotic way. All over the earth this aboriginal planting has been done away with. The earth has been made to be like a girdled tree and here in my home in the west is the last small ribbon of bark… I am sick at heart to have sneaked around like a criminal for 25 years doing this.” She continued carrying bags of seed with her everywhere she went, enlisting others to help with this work.

Finisia Medrano was no conventional environmentalist. Her approach was not incremental; it was radical and uncompromising. Her life defied narrative and transcended all conception of what is possible. She was complicated, she could be surly and rude, her language sometimes alienated people, and yet her love for the Earth, her vast knowledge of the plants, animals and landscapes of the West, her generosity at sharing this knowledge, and her ability to be a friend, even from a long distance, were unparalleled. Finisia, despite having her eyes open to the destruction wreaked by humans upon the planet, never gave up.

A few days before she died she was out planting fruit trees in Nevada with two friends. On April 1 she felt what she thought was a heart attack. The following day, another. The next day she died, a mere 150 miles from where she was born 64 years earlier in Las Vegas—completing the ultimate Hoop—death taking her life so close to where it had begun. She will be missed by the land in the West and all livings beings who thrive there.

____________________________________

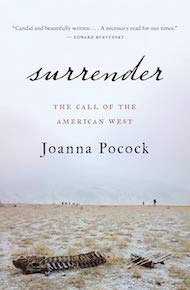

Finisia Medrano features in Joanna Pocock’s award-winning book Surrender, a work of hybrid narrative non-fiction blending memoir, reportage and nature writing examining subcultures who live close to the land in the American West. It was published in the US on April 7, 2020 by House of Anansi Press.