In this story, you get to be the sansei heroine because you are like a lump of narrative Play-Doh, and the less self-awareness you possess, the more you can be poked, prodded, and punched into possibility. You are the heroine because we follow your adventure even if other characters might have better adventures and more interesting lives, because your adventure has moral authority, and because it’s a trick. This is not said to make you feel special or bad or even tricked; the real story is there, just not necessarily in your exact direction.

Mukashi, mukashi, Cathy Ozawa grew up a tomboy, but then around adolescence got it together to pretend to be a girl. In those years, girls did a lot of pretending. Let’s pretend Barbies. Pretend your Barbie and my Barbie live in castles right next door. Pretend that Ken lives with your Barbie one week and my Barbie the next week. There’s only one Ken, so they take turns. Sometimes your Barbie and my Barbie live in the same castle, which is way more fun. Sometimes our Barbies leave Ken all alone in your castle wearing your Barbie’s clothing because Ken only has one set of clothing, even if it’s glitter pants and a jacket, but the shoes never fit. The only way to make the shoes fit is to screw Ken’s head onto your Barbie’s head or vice versa. OK, if you let your imagination run, you get the pretend picture.

The real story is there, just not necessarily in your exact direction.Cathy grew up in Fullerton with white people who had escaped the darkening inner city. As it turns out some J.A.s, too, escaped into the burbs of scattered cities across the US., since returning from concentration camps to the confinement of ghettoed j-towns didn’t seem like an option for the future. And if J.A.s just spread out all over the country, maybe the next time around, it would be harder to find them. Besides, Mr. Ozawa had served America honorably during the war, using his language skills for military intelligence, interpreting and breaking Japanese codes, linguistic and cultural. Not that anyone knew this; it was a secret. Those white neighbors who chafed at having to live next door to the only Japanese family within miles could wonder at their luck, but Mr. Ozawa conducted himself with a mixture of friendly and aloof dignity, because he had the upper hand of conscience that patted him on the invisible stars of his kibei shoulders.

By the time he was known as Ol’ Man Ozawa and had trained several generations of white karate kids, even his own kids were surprised to read their dad’s obit. Jim and Cathy Ozawa went through childhood and adolescence like it was normal to be white, until one day Jim left for college to study Asian American studies at UCLA and Cathy drove her mother’s elderly friends Mr. and Mrs. Ishi to a dental appointment in Little Tokyo. Mrs. Ozawa said to Mrs. Ishi, “Cathy just got her driver’s license.” She searched for a plausible excuse in case it turned out to be a bad idea. “She’s never even been to Little Tokyo.”

“Oh,” replied Mrs. Ishi, “I’m sure she’s a very safe driver. Never been? Oh my.”

“Tosh and I go. You know, funerals and maybe Nisei Week, but we never bring the kids,” Mrs. Ozawa replied defensively, but the kids weren’t kids anymore.

Mrs. Ishi pouted, then recuperated her natural optimism. “It will be an adventure. You know, I never learned to drive the freeways, and Woody’s eyes just aren’t trustworthy anymore. Cataracts.” She blinked for emphasis and sighed. “When we moved out here”-she waved her hand around like it was all Disneyland in a Midwestern cornfield-“we changed all our doctors, but we just couldn’t change dentists. Am I wrong, Mary? Living out here all these years, you probably don’t have a Japanese dentist, but I couldn’t trust just anyone inside my mouth.” Mrs. Ishi moved her lips over her crooked teeth, sported an apologetic smile, then continued, “And besides, we like to eat in Little Tokyo and stock up on provisions.” By provisions, Mrs. Ishi meant Japanese foodstuffs: Calrose rice, shoyu, rice vinegar, miso, sake, nori, bancha, ajinomoto, etcetera. “Don’t forget to send Cathy with your list.”

Mrs. Ozawa put a list into her daughter’s hands, not without noticing the black fingernail polish and the blood-ruby ring attached by a delicate chain to an ornate black lace bracelet. As usual these days, Cathy was dressed in black-boots, jeans, tee. Mrs. Ozawa queried her daughter’s face, and Cathy reassured her, “I didn’t apply it that thickly today, Mom. Don’t want to scare the Ishis.” Cathy was really the sweetest young woman, and Mrs. Ozawa prayed everyone would see her daughter through that dark outfit.

Cathy resisted the urge to turn on kroq and drove the Ishis’ gray Buick with conscientious attention, darting eyes checking mirrors and merging like a cab driver, Mr. Ishi at shotgun and Mrs. Ishi in the back seat and chattering nonstop with great particularity about the Lakers-the players, their positions, averages, heights, injuries, scoring patterns, prospects for the semifinals, and on and on.

When Mrs. Ishi seemed to be catching her breath, Cathy turned to her husband. “Are you a fan, too?”

“Oh yes, but she’s the expert. I just took her to her first game.”

Mrs. Ishi pounced back in, leaning forward into the gear shift. “That was when Woody could drive. UCLA versus USC. From that moment on-” Mrs. Ishi paused rather romantically.

And Mr. Ishi finished as if responding to a song, “It’s all history.”

“My brother Jim is at UCLA,” Cathy offered.

“What’s he studying?” Mr. Ishi queried.

“Sociology, I think.”

“Smart kid,” Mr. Ishi remarked.

“That game at UCLA,” Mrs. Ishi returned to her subject. “I first saw Lew Alcindor . . .”

“Kareem Abdul-Jabbar,” Mr. Ishi corrected.

“It was like,” Mrs. Ishi searched for the right word and landed on, “ballet.”

Meanwhile, Southern California whooshed by until they descended an off-ramp into that iconic cluster of downtown high-rises hugged by a floating donut of smog. As Mrs. Ishi had promised, it would be an adventure. As instructed, Cathy dropped Mr. Ishi off at his dentist on First Street, then proceeded on to Third with Mrs. Ishi, who wanted to visit her friend Mrs. Murata at the Hiroshima Café. “I’m surprised your folks didn’t at least bring you here,” Mrs. Ishi remarked to Cathy as the door opened and chimed behind them. “Min and Mitoko are old friends. Opened this place right after the war.” She strutted over to a booth in the corner, settled into the red Naugahyde, and leaned over the table, whispering to

Cathy conspiratorially, “Chashu ramen.”

A young woman with a pad sauntered over to the table and exclaimed, “Mrs. Ishi, where’s mister?”

“Bella.” Mrs. Ishi smiled exaggeratedly, showing her canines. “Woody’s doing his teeth.”

Cathy’s eyes traversed the Hiroshima hostess Bella, who sported a red happi coat over a leather skirt and fishnets, her hair ratted in every direction. “Tsk tsk.” Bella shook her finger at Mrs. Ishi. “Too many sweets.”

Mrs. Ishi nodded back and forth like it was her fault. “Bella, this is Cathy.”

Bella took a step back and glared appropriately through mascara and thick eyeliner, moist red lips articulating, “How do you do?” emphasizing the do’s.

“Uh,” Cathy stumbled. “I don’t. I mean-”

Bella turned and left the table, yelling over the counter into the kitchen, “Momma, guess who’s here?”

Mrs. Murata emerged from the kitchen rubbing her hands on her apron and scooted into the booth next to Mrs. Ishi. Cathy watched the ladies turn into little girls again.

“How’s Min?” Mrs. Ishi asked.

“Not so good. Can’t talk hardly. Can’t use his right side.”

“My brother had a stroke too,” Mrs. Ishi commiserated.

She couldn’t believe her luck. What sort of café was this? There was no such place in Fullerton. Fullerton was a cultural desert.Mrs. Murata pushed gray hair under a stretchy net. “I’ve got to go home and feed him now.” She looked around the café. “Bella’s taking it over.” Without bothering to ask, Bella came around with bowls of chashu ramen, then walked over to the jukebox and punched in what Cathy recognized as Siouxsie and the Banshees. She scanned the walls plastered with band posters and concert flyers, picking out her favorites. She couldn’t believe her luck. What sort of café was this? There was no such place in Fullerton. Fullerton was a cultural desert. The door chimed in tune to Siouxsie’s oriental song, Hong Kong Garden, and they all looked up. Mr. Ishi appeared dejected.

Cathy knew all the words: disoriented you enter in / unleashing scent of wild jasmine.

“Woody,” Mrs. Ishi suggested, “show us your smile.”

“Got to come in next week again. Root canal.”

Cathy couldn’t help herself. “No problem at all!”

Bella’s eyes caught Cathy’s. Bloody lips parted in a cruel grin, message sent and received. Slanted eyes meet a new sunrise / a race of bodies small in size.

Cathy shut her eyes and sucked in, one egg noodle sliding between her teeth, salty wet tail disappearing into a puckered O.

*

The summer started like that, back and forth for Mr. Ishi’s teeth, provisions, and chashu ramen. The Hiroshima Café was, let’s say, an eclectic dive, where all sorts of human beings happened along: the regulars from the local community, retired migrant workers looking for a cheap meal, aging beatniks and deadbeats, day laborers, local yakuza, and now Bella’s cohort of activist anarchists, jivers, musicians, and, lately, punks, post- punks, goths, or whatever the scene was that outdid the previous, plus scattered unsuspecting tourists. Eventually Bella proposed to Cathy, as if an afterthought, waving a cigarette, “We could use some help. I can pay you by the hour, but . . .” She paused to think. “If you do your eyes bigger and badder, you’ll probably make more in tips.” A job sounded legitimate, but Mrs. Ozawa was suspicious, because who goes to work plastered in makeup with fishnet stockings and spiky hair? So she sent Cathy’s older brother, Jim, on forays to Little Tokyo from ucla. “Mom, relax. Relax. Don’t you know the Muratas? I go to school with the son, Jonny Murata.” What he didn’t tell his mom was that he was soon also dating Bella, if what- ever relationship they were in could be called dating.

Whenever possible, Jim and Jonny were at the café, usually for lunch or dinner. “Beats dorm food.”

“I bet. You might at least,” Bella smirked, “leave a tip.”

Jim looked at Jonny. “What say we unionize the workers here?”

Jonny sneered. “Minimum wage, bullshit. Who do the Muratas think they are?”

“Putting you through college, dope.” Bella rolled her eyes.

Jonny pranced around, shouting, “On strike! On strike!” He returned to the table and shoveled down a plate of egg foo yung and said to Jim with his mouth full, “I could use this place in my paper about Asian family restaurants, child and cheap labor. Be an exposé. Hey, I lived this shit.”

“Jonny, you never lived no shit.” Bella’s eyes drilled into her brother’s.

“I live this shit.”

Jonny grumbled at Bella’s behind as she walked away, but Cathy returned with a tray of glasses and two cold bottles of Budweiser.

“Cathy,” Jonny began, “when do they give you a break? I got my Supra right here beyond that door, waiting. Purring. You know what I mean? The meter’s ticking. If you wait too long, I could get a ticket. Tick tick tick. Make up your mind. I can take you away from this chungking ichiban fast.”

Cathy smiled. “If you drink that Bud and drive away, you can get a ticket too.” She stepped away to the next booth.

Jonny raised and knocked his glass on Jim’s and took a slug of Bud. “Talk to your sister. I know she likes me.”

“She doesn’t like you, Jonny.”

“No, Jim. She’s falling fast. Any minute now.”

“Forget it. She’s in high school. Way too young.”

“Egg fool young! You’re doing Bella. Do I say anything?”

“That’s different.”

*

One day, Cathy walked to a booth, its table covered with intricately and realistically painted watercolors of fruits, vegetables, and flowers. A young man was turning the paintings in his hands, then placing each carefully back into a folder. “These are great, Nora,” he said sincerely to the young woman across the table. “When did you paint them?”

Nora shifted in the seat, and Cathy thought she answered, “In the can. Except”-she pointed at another group-“for these. I did them lately.” She looked up at Cathy, who, pad in hand, was quietly observing.

“Oh,” said Cathy, “I can come back later.”

“No, thank you, we’re ready.” The young man pulled out a menu from under the paintings.

Cathy looked the couple over with interest. They were local sansei, dressed casually in jeans, probably Jim’s age. This was their territory, Cathy thought enviously. They had grown up knowing this place and each other. The woman wore no makeup. There was a tough, determined, but sad air about her, a quality Cathy admired in Bella. Nora could have been Bella without all the makeup.

“Henry,” Nora said, “I’m not that hungry. Choose something, and I’ll eat some of it. Anyway, I got to get back and do that class.”

Henry nodded and ordered the chicken chow mein and tea.

Cathy nodded. “Sure.” She looked back at the table, Henry’s black pony- tail swirling down the back of a worn t-shirt over the words Manzanar Pilgrimage.

Returning to the table with tea, Cathy ventured shyly to Nora, “You’re so talented.”

“Thanks.”

Henry suggested, “Nora’s teaching classes at the cultural center. Interested?” He handed a flyer to Cathy. “Maybe you could put this up?”

When Cathy handed the flyer to Bella, Bella said, “Nora Noda is back.”

“What’s that mean?”

“Means she’s on parole.”

“Oh.”

“You wouldn’t know, but Nora went underground doing shit like building bombs to start the revolution, and then she got arrested, and now she’s doing community service. We’re her community.” Bella smiled her nasty smile. “Nora’s my heroine. If I could do what she did . . . but who has her guts? Easier to do this.” She waved her arms around the café. “Oh, and since you seem interested, that sweet sansei guy Henry is her brother. He chauffeurs Nora around to keep her out of trouble.” She puckered her lips. “Toot sweet for me.”

That evening, Cathy stuck around to do the evening shift because Jim had promised he could drive her home late. Bella got herself into full costume with a black-and-red bodice hugging her breasts and everything showing lasciviously. She handed Cathy a bag. “You need to dress up for the night.”

Cathy rummaged through the bag: black gloves, black lace cascading from a tiara, crucifixes, a whip. She pulled out a jar.

“Oh that.” Bella pointed a pointed nail. “You’re gonna love it. Genuine kabuki face paint.”

The café filled up with all these white kids in leather, lace, safety pins, and chains, maybe from Fullerton, dressed to kill, and Cathy felt ecstatically important, maneuvering with trays and plates, until some guy made a pass at her, cooing, “China girl, you don’t even have to dye your hair.” A rumor spread that band members from Christian Death were there, interrupted by a second rumor that Sid Vicious was there. Then someone yelled, “You idiots! Sid Vicious is dead!” The entire café erupted into the chant Sid Vicious is dead! Sid Vicious is dead!

Bella strutted to the jukebox and sent the anthem charging through the café speakers: “Bela Lugosi’s Dead.” Bella pranced back into the aisle and screeched, “BELLA!” to which the entire café crowd responded in unison: Lugosi’s dead!

“BELLA!”

Lugosi’s dead!

Then, undead, undead, undead!

In the midst of this, Cathy saw Henry Noda arrive with another guy who could have been his twin. “You’re back.” She smiled.

“We never got introduced,” Henry said, though considering the new layer of kabuki makeup, she could have been anyone.

Bella came by. “Hey Fred,” she addressed Henry’s companion. “Hey Bella.”

“My brother, Fred,” Henry said to Cathy, watching Fred walk away with Bella.

Henry sat by himself, and Cathy came back and forth between serv- ing patrons.

“I’ve never been here late,” admitted Henry.

“Me neither.” Cathy shrugged.

“Really? I thought you were the kabuki girl.”

“Oh, that must be Bella.” She looked up to see her brother, Jim, arrive and frowned to see Jonny.

Jonny swaggered over to the table. “Hey Cathy, working tonight?” Cathy shot up from the seat and left quickly. The guys slid into the booth.

In the kitchen, Bella and Fred were frantically making out, groping and tugging, tragically on the verge, boiling broth spilling over the pot. The cook had probably left for a smoke. Cathy tiptoed away, even in platform boots, and said to Jim, “Maybe you should take me home now.”

“Yeah,” he answered. “But let me talk to Bella first.” Before Cathy could object, Jim had left the table to look for Bella. Predictably, a crash of plates and pans and shouting came from the kitchen, though no one could hear it over the jukebox.

Leaving to assess the situation, Jonny sauntered back almost victoriously and announced, “Cathy, it seems Jim is a bit, shall we say, indisposed, but I can drive you home to Fullerton. No problema. Turbo horsepower at your service.”

But Henry said, “Jonny, you’re drunk,” and pushed him. To Cathy’s surprise, Jonny fell over.

“Come on, Cathy.”

At midnight, the freeway was a dark eternity into starry headlights, eighty miles an hour, a swift blur through white and red. “I love the night,” she said.

“I work the night,” he said. “I don’t see daylight.”

“But I saw you at lunch today.”

“Helping my sister.”

“And your brother?”

“Can’t help him. Messed up. Ever since he returned from Nam. Stupid stuff like tonight.”

“What work do you do?”

“Produce market with my dad. Get the stuff to market before the morning.”

She chuckled. “I thought you might be a vampire.”

“You wanna interview me?”

“Did you read it?”

He laughed. “If I lived way out here, I’d be reading Anne Rice too.”

“But you know the book?”

“Do you want a reading list? I read everything. Keeps me from going crazy.” He drove awhile in silence, then asked, “Why do you want to be the kabuki girl?”

“What do you mean?”

“Bella I get, but you?”

*

OK, so we got our heroine and hero in a car at night cruising the L.A. freeways, talking about life’s choices. The hero’s sister chose the revolution, but it never happened. The hero’s brother chose the military, but that too never happened, well, like he expected. Turned out he was mistaken for the enemy, and it was true; the enemy looked like him. After he killed people who looked like him, he came home, and no one thought he was a hero, least of all himself. Meanwhile, the hero stayed home to take care of his widowed dad, a silent and bitter man who felt shunned by his community. And with kids like that, he thought, what was the point? Then there was the heroine’s brother, who went after chashu ramen like he was going to get the chashu but only got stuck with the white pepper dregs at the bottom of the bowl. And the heroine’s new friend, who chose to try to save the family business, and her brother, who wouldn’t know a choice if it were placed in front of him. As for the heroine, catching her own flashing reflection in the dark windshield, she touched the chalky, super-white surface of her cheek and began to wonder on that midnight drive home if she were not still pretending.

*

Toward the end of summer, Nora Noda had a small art show with her students in the gallery space of the Little Tokyo cultural center. Cathy drove the great gray Buick and Mr. and Mrs. Ishi into town to see the show. Henry was busy taking photographs.

“Oh,” exclaimed Mrs. Ishi, “such a lovely display.” She was especially appreciating the drawing by a second-grader of a basketball player in a jump shot. “Woody.” She tapped her husband on the elbow and pointed. “There’s Katz Noda. We haven’t seen him in years. He never comes to anything. He must be so proud of-well, relieved over Nora’s success.”

Mr. Ishi hailed Mr. Noda. “Hey there, General. It’s been years.” Mr. Noda nodded.

Mrs. Ishi pulled Cathy over. “Cathy, you should meet the General. Oh, he’s not a real general. They just call him that because he runs the produce market. He’s just a gruff sort. Don’t be afraid. He’s an old friend of your dad’s. He’ll be delighted to meet you.” Pushing Cathy forward, Mrs. Ishi announced, “Katz, you should meet Cathy, Tosh Ozawa’s daughter.”

The General seemed to blanch, his face turning visibly sour. Before Cathy could speak or stretch out her hand, he turned, walked away, and left the gallery.

“Oh dear,” said Mrs. Ishi, but Mr. Ishi only shook his head.

Henry, having witnessed the scene, came over to make small talk, but Cathy wondered what Bella would have done. Cathy had toned down her makeup, put on a semblance of normal clothes, removed her lip ring, all for nothing. Oh well, the summer was ending, and so would this episode in her life. She could go back to her normal life and leave these J.A.s to theirs. Obviously she didn’t fit. She walked over to a table strewn with square colored papers. Nora was there with a group of children. “What are you working on?” she asked.

A girl looked up. “Paper cranes. Nora says we need to make one thousand.”

“How many have you made?”

“Two. Can you help?”

“Sure.” Cathy picked up a crane and examined it with curiosity.

“Don’t you know?” The girl made a small huff of exasperation. “So first you fold it this way.”

*

But there was one last night at the café. Well, you were there, so you should know what happened. Bella was in high form, queen of the night, and by now she had switched her affections to Fred, who generously divided his drugs with her, so they were continually in a zone. Jim wasn’t there; he’d retreated to school and scholarship, headed futuristically for his PhD. Jonny was there playing craps in the summer night with the punks on the sidewalk outside the café. Inside: the usual commotion of chop suey, white skin, black hair, and dilated pupils. This was going to be Cathy’s sayonara night. She was still an innocent high school girl observing the scene sober like one day she would write about it, but some idiot in the third booth yelled at her. “Fuck this egg fuk yung!” and flung a piece of it her way. She picked it out of her bodice and mashed the egg hash into his pimply face. Maybe it was her fault. And that’s how it started. Egg foo yung flying this way and that. Noodles colliding in air with Buddha’s delight and fried rice. When Cathy crawled out of the chaos, she could see Bella splashing tea and beer into faces and dragging the fools out. Cathy slipped around in grease and soup and managed to get out the door. Outside, Jonny was pacing around and screaming about his Supra. His beloved Supra, the only thing he really cared about. He’d lost it to craps. Predictably, just at that moment, our hero arrived.

Henry grabbed Jonny. “Where’s Bella? Why don’t you answer the phone in there?”

Cathy stumbled forward, slapping bok choy from her shoulders, and Henry stared at the noodles laced through her spiked hair. Well, that was the night Min Murata had a second stroke and died.

Like Mary Ozawa had admitted to Mrs. Ishi, she and Tosh only went to Little Tokyo for funerals and, maybe, Nisei Week. But this time, their kids, Jim and Cathy, came along, though folks must have glanced side- ways at Cathy’s version of formal black funeral attire. The family sat solemnly in the front pews and followed all the rituals, listened to all the stories about Min and his wife and the Hiroshima Café. And that’s when Cathy found out that Min Murata, Katz Noda (the General), and her dad, Tosh Ozawa, were all kibei educated in Hiroshima before the war, that the three had been close buddies who banded together to ward off bullies because they were considered neither really Japanese nor really American. When they returned to America just before Pearl Harbor blew up, each made different decisions that changed their lives forever. Min Murata left for Montana and opened a Chinese café, avoided camp. Katz and Tosh got hauled off to camp, but when the loyalty questions came up, Katz checked no and Tosh checked yes. The two got into a heated argument and never spoke to each other again. Katz renounced his citizenship and went to Tule Lake, and Tosh signed up for service, got sent to Fort Snelling, and prepped to be an interpreter in the Pacific.

After Min’s funeral, folks gathered at the café. After forty years, Katz and Tosh sat together, an uneasy truce, deep in a red booth next to the jukebox, Min’s old enka music dropping in one forty-five after another. A draping spray of black origami cranes cascaded from the ceiling above. They looked out at the J.A. crowd, all eating chow mein and fried rice between what Mrs. Ishi called “Bella’s Halloween posters.”

Katz broke the silence and nodded at Jim and Cathy. “Nice kids.”

“Sanseis,” Tosh muttered. “Think they know better.”

“Rebels.” Katz took a sip of tea. “I should know.”

“Yeah.” Tosh knew. He read the Rafu. “Henry turned out.”

“Should have left after the wife died. Thought he should take care of me. I can take care of myself.”

“Fred survived the war.”

“That’s saying a lot. I told him not to go, but you know that argument. Stubborn like you. Said he wasn’t going to be a coward like me.” Katz’s eyes filled.

Tosh closed his eyes and spoke into the table. “Didn’t know what he was talking about. Don’t be so hard on him. He saw stuff. It doesn’t leave the mind. I should know.”

Mitoko Murata came to the table, dressed in a simple but stunning black silk shift, white pearls hugging her neck, elegant and still beautiful. The men rose. She put her hands into theirs and squeezed.

*

So pretend for a moment you’re American. Pretend you’re Japanese. Pretend you’re nisei. Pretend you’re kibei. Pretend you’re sansei. Pretend if you mix and shake it up enough, no one will know the difference, that even you won’t know.

__________________________________

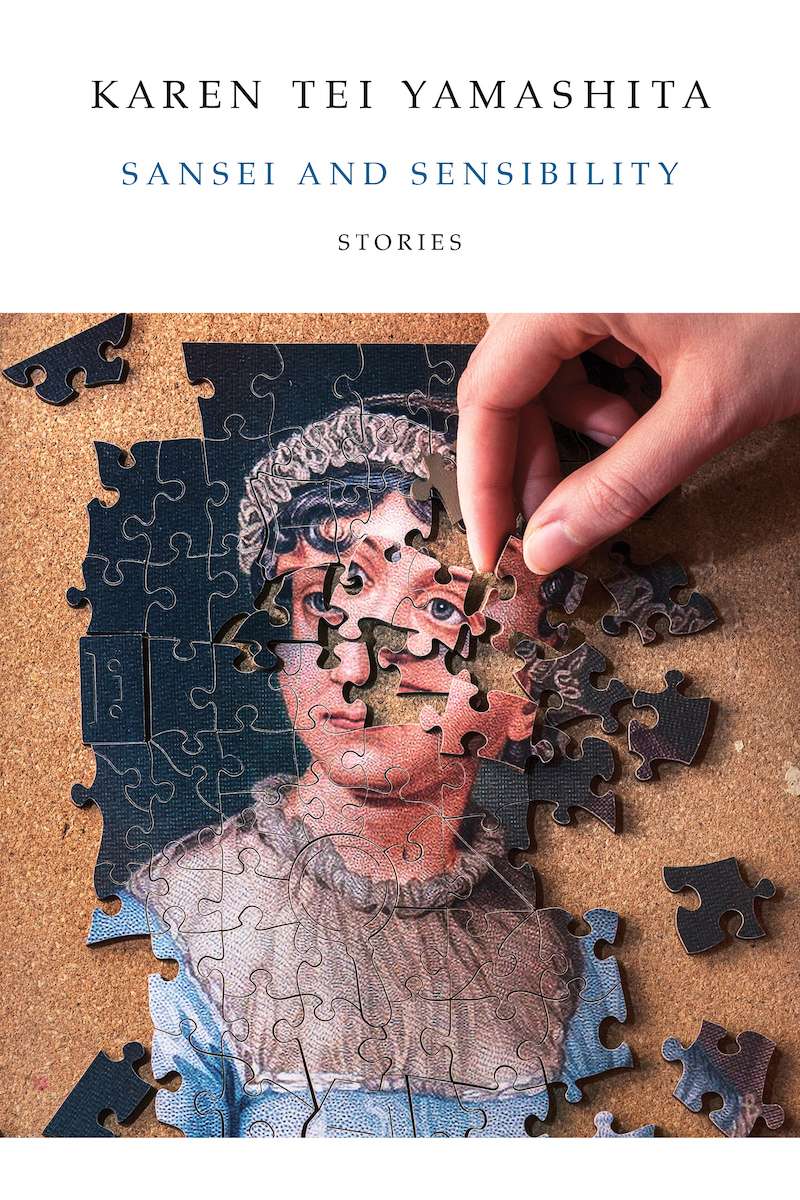

Used by permission from Sansei and Sensibility, published by Coffee House Press. Copyright © 2020 by Karen Tei Yamashita.